Our oceans are choking on plastic, but researchers in Civil Engineering are determined to change this in a generation.

The images are horribly familiar – turtles enmeshed in polythene bags, whales choked by shoals of plastic waste, a beautiful ocean wilderness blanketed in the jetsam of the developed world. Dr Costas Velis, Lecturer in Resource Efficiency Systems, and his research team have been instrumental in crunching the numbers behind the story of plastic pollution, recently brought to global attention by Sir David Attenborough.

They project that, without urgent action, between 2016 and 2040 almost 1.4 billion tonnes of plastic will end up dumped on land and in watercourses. Another 2 billion tonnes will be burned in the open, releasing toxic fumes and greenhouse gases.

Costas first became aware of the issue as a teenager: “I grew up in a small fishing town in Greece, surrounded by the sea and a vast complex of lagoons – a protected bird habitat of international importance. Yet, the local authority would dispose of waste into the wetland, or set it on fire on a nasty dump site. When the wind blew in the wrong direction you could smell it across the whole town.

“It was a total paradox,” said Costas. “This is a place which had preserved its ways of life, its fishing and agriculture, for centuries – and yet at the same time was doing enormous damage to the environment. When you see this going on, in some of the most beautiful places of the global south, like the Brazilian rainforest, in informal settlements in Kenya and Indonesia close to stunning natural reserves, it’s deeply unsettling.”

A computer model co-developed by Costas, Ed Cook, Research Fellow in Circular Economy Systems for Waste Plastics, and a group of expert colleagues worldwide has tracked the flow of plastic across the globe and revealed systems overwhelmed by the sheer volume of plastic waste.

A key issue is the amount that simply isn’t collected – around two billion people worldwide have no formal waste collection. “We take rubbish collection for granted,” he said, “but what can you do if no one comes to take it away? People throw it in the street, in a creek, in the sea, or just set it on fire. What choice do they have? The rivers themselves become polluted environments, transporting waste to other people downstream and on into the oceans.”

There are further consequences. “As drainage channels become overwhelmed by discarded waste, their effectiveness is also disrupted, causing flooding. We also know that these plastics are breaking down and just one single object can become millions of fragments. It’s shocking to think that microplastics are already everywhere – in the air, in the soil, in our food and our drinks. Whilst the jury’s still out on the implications for human health, the facts are massively alarming: we need to stop it, and do so at source, before it breaks down, enters the environment and is dispersed all over.”

The impact goes beyond the natural environment. “We worked to model plastic pollution for Bali, one of the world’s major tourist destinations, which relies heavily on its pristine environment for visitors. Plastics on the beaches and in the sea have major economic implications for the island.”

Any intervention begins with taking individual responsibility for what we use and how we consume it – whether that’s taking a reusable water bottle to the gym or separating waste so it can be efficiently recycled. However, Costas warned: “These alone aren’t going to solve the problem.”

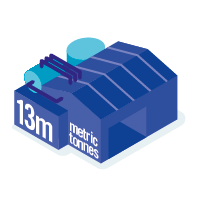

Rather, the joint report Breaking the Plastic Wave (see graphic below) asserts that the issue can only be tackled with concerted, joined-up and sustained intervention by government, industry and society worldwide. The report’s System Change scenario sets out a series of complementary interventions to reduce plastic pollution by 80 per cent over the next 20 years: “There are pathways we can take to bring this under control within a generation,” he said.

Reducing plastic consumption is an obvious first step, but while government initiatives around the world have focused on bottles and shopping bags, the report depicts a more complex picture. Vast populations of the urban poor, notably in Africa and South East Asia, have no option but to consume food and products such as shampoos in tiny, highly polluting, sachets and films. Moving away from such packaging could have a much greater impact. Similarly, the report suggests that some plastic products can be safely and economically replaced by paper and compostable materials.

But where plastic remains the only viable option for a product, more must be recycled or, failing that, recovered as fuel. Currently only small amounts of plastic can be practically recycled – switching to those that can be economically reprocessed, while improving labelling so that used products can be better sorted for recycling, could massively reduce the amount that ends up as waste.

The team’s modelling shows the effectiveness of these interventions: every extra tonne of plastic collected would prevent 180 kilograms of waste reaching the aquatic environment. So investing in waste collection, particularly in low- and middle-income countries, would both address the issue of waste reaching the oceans and improve the lives of some of the most disadvantaged people on Earth. Increasing the tiny amount of development aid that goes to the waste and resources management sector is critical to this change.

“At the same time, we can empower the waste pickers to help us solve this global challenge,” said Costas. “Across the global south millions of marginalised people work on dump sites and search in bins to salvage recyclable items. Like the old rag-and-bone men, they pick things which have value – perhaps a PET water bottle or a PP yoghurt pot – and sell them to someone else who trades them further down the chain. By doing so they are actually preventing plastic from becoming pollution. They are unsung heroes, responsible for the greatest proportion of plastic recycling worldwide.

“Theirs is an unimaginably hard life, yet they’re bringing plastics back into the economy in places where state waste collection for recycling doesn’t exist. By recognising their role, formalising their employment and improving their conditions, we can support them to prevent plastic pollution.”

We still need to rapidly increase the amount of plastic waste that is mechanically recycled, a figure currently running at around 15 per cent. Allied to improved collection and sorting systems, investment in new recycling plants around the world could increase that figure dramatically, cut greenhouse gas emissions, and generate revenue as recycled plastic is sold on for re-use. Innovation in chemical conversion can lift this figure still further, increasing the range of low-grade, heavily-contaminated plastic which can be converted into new materials.

Yet even with these measures in place, the report concedes that investment will also be needed to create engineered and controlled landfill sites to house the vast volumes of plastic that still cannot be recycled or reused. Coupled with this is the need to reduce the 3.5 million tonnes of plastic that high-income countries export annually to middle- and low-income countries where there is a greater risk of it being openly burned or illegally dumped.

Recent media coverage has propelled this into public consciousness. “There’s been a fantastic wave of awareness,” said Costas. “And because we’re all aware of the plastics we use and discard, the damage we’re causing is much easier for people to understand than carbon dioxide, which is invisible.

“But awareness is only one part of it. This is an issue which demands system-wide approaches.” Beyond academia, Costas works with international forums and organisations, leading the Task Force on Marine Litter of the International Solid Waste Association. He has also backed demands from the WWF and Ellen MacArthur Foundation for a binding UN treaty to slash the amount of plastic waste reaching the environment.

“The work we have released shows – in the strongest possible way – that we are facing a major global challenge. We can’t hide from this, we can’t ignore it. It is so serious that we need concerted and immediate action,” he said. “Without it the problem will keep escalating at a worrying pace. This should by no means divert our attention from solving other established global challenges, such as climate change and the loss of biodiversity.

But it needs adding to that list.”

Will that problem be solved? “I believe in human ingenuity and that through our ingenuity we can solve the problems we’ve created,” Costas said. “I think here of the fight against ozone-depleting substances, where we seem to be winning! But this requires everybody – the innovators, companies, governments, academics, practitioners and people who fund development aid – to work together.

“I am inherently optimistic,” he said. “But my optimism is cautious, because the change we need to see on the ground is substantial.”

Working alongside colleagues from global innovation group SYSTEMIQ, the University of Oxford, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation – established by the record-breaking yachtswoman – and campaign group Common Seas, Costas Velis has produced the report Breaking the Plastic Wave. Published by the Pew Charitable Trusts, this scientific inquiry offers the first comprehensive insight into the amount of plastic being dumped in global ecosystems.

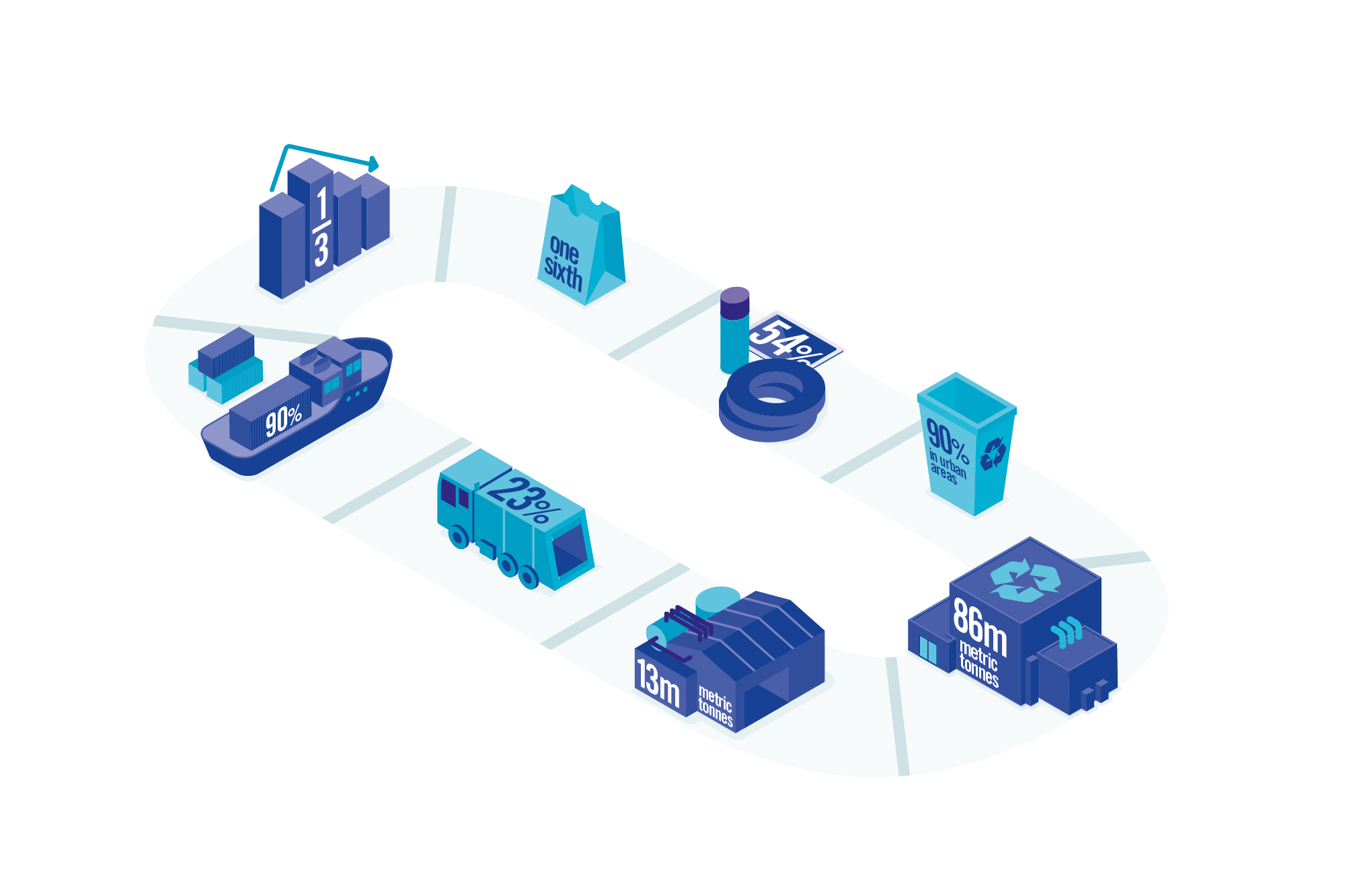

1. Reduce

growth in plastic consumption to avoid nearly one-third of projected plastic waste generation by 2040

2. Substitute

plastic with paper and compostable materials, switching one-sixth of projected plastic waste generation by 2040

3. Design

products and packaging for recycling to expand the share of economically recyclable plastic from an estimated 22 per cent today to 54 per cent by 2040

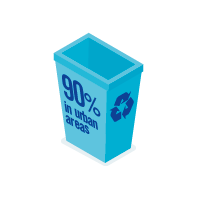

4. Scale up

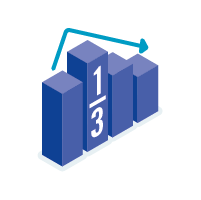

collection rates in middle/low-income countries to at least 90 per cent in urban areas and 50 per cent in rural areas by 2040

5. Double

mechanical recycling capacity globally to 86 million metric tonnes per year by 2040

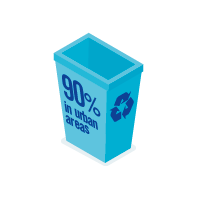

6. Develop

plastic-to-plastic conversion potentially to a global capacity of up to 13 million metric tonnes per year

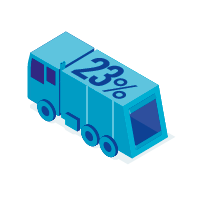

7. Dispose

securely of the 23 per cent of plastic that still cannot be economically recycled

8. Reduce

waste exports into countries with low collection and high leakage rates by 90 per cent by 2040

Mohamed Kamal (BEng Civil Engineering with Project Management 2018; MSc Water, Sanitation and Health Engineering 2019) examined the level of plastic waste flowing into the Nile from an informal settlement close to Cairo.

A scholarship funded by alumni enabled Mohamed Kamal to study on the University’s renowned MSc in Water, Sanitation and Health, while a travel bursary supported his fieldwork examining plastic waste in Egypt.

Through questionnaires and interviews with residents and local waste professionals, and examinations of the types of waste and its disposal, Mohamed unveiled a series of key issues around solid waste in the region.

After graduating with a Distinction – and the highest marks in his cohort – Mohamed spent two months volunteering on a project to clean areas of the Nile before taking up a post at Nahda University in Egypt to work on waste management research. “I truly cannot put into words how big a role this scholarship has played in helping me be where I am today,” he said. “My promise is to never forget the privilege I have had through my education and to make the most of every opportunity.”

The University and Leeds University Union (LUU) pledge to become free of single-use plastic by 2023.

With catering and office spaces already single-use plastic free since last year, support is now being given for lab space and other services to develop alternatives to disposable plastic equipment over the next two years.

“This is a huge commitment and a big challenge for us,” said Dr Louise Ellis (PhD Earth and Environment 2008), Director of Sustainability. “But we are determined to play our part by acting together to reduce our plastic footprint.

“We’ve already made so much progress, through strong recycling rates and catering initiatives such as our reusable cups. We hope this pledge inspires all staff and students to contribute towards reducing our use of throwaway plastics across campus and beyond.”

Chris Morris, Union Affairs Officer at LUU, added: “Students have often been ahead of the national agenda, with Freshers’ Week being plastic bag free and ensuring we have biodegradable alternatives in the Union. We look forward to working in partnership with the University to make sure we all have a positive impact on this future-defining issue for the planet.” The University and Leeds University Union (LUU) pledge to become free of single-use plastic by 2023.